What do we know about Asian New Music? In Conversation with Ali Fyffe

Forest Collective’s saxophonist and improvisor Ali Fyffe has spent significant time in Asia, collaborating and touring with a wonderful array of musicians, composers and arts venues across numerous countries. She drew on those experiences when programming Forest’s upcoming concert Asia in Focus, and shares some of her reflections on the vibrancy, energy and complexity of the Asian New Music scene. This is something that is not very well understood in Australia.

“Often people ask me if I was teaching music when I was in Asia,” Fyffe says, “I reply: ‘I wasn’t teaching, I was learning and collaborating.’ They can’t believe it when I tell them about the amazing innovation I saw there.”

This sense of white cultural superiority – a hangover from colonial times – is still alarmingly present when she talks to people about her time there.

“People ask things like: ‘What do you mean, you collaborated on contemporary classical music and improvisation in Asia? Aren’t we the innovators here in Australia, not them?’ That’s the attitude I get a lot.”

Fyffe buzzes with energy as she recalls the exuberant creative spirit she experienced during her years in Asia, mentioning Thailand as a prime example.

“The late King Bhumibol Adulyadej was a fantastic jazz saxophonist and composer,” she explains, “So saxophone and improv are really valued and celebrated there, especially in Bangkok!”

Candelight Blues, composed by the late King of Thailand Bhumibol Adulyadej.

Even in countries with more oppressive governments, contemporary classical music is thriving.

“When programming Asia in Focus, I really wanted to include an Iranian composer,” Fyffe says. “I find it absolutely fascinating that out of all the music that has been banned in Iran since the 1979 revolution, contemporary classical western music is still allowed. I’m thrilled that we can present the world premiere of Alireza Farhang’s La Voix Etherée.”

While in modern Iran there are complex issues about women being allowed to play music – Fyffe chose not to bring her saxophone with her to Iran for this reason – the country has a strong historical connection to contemporary classical music. The Shiraz Arts Festival, which ran from 1967-77, fostered an incredible confluence of artists and musicians from all over the world, including the likes of Karlheinz Stockhausen, Morton Feldman, Arthur Rubenstein and Yehudi Menuhin.

It was described at the time as ‘the most important performing arts event in the world’ and included performances by some of the greatest exponents of the European, Persian and North Indian classical traditions. Ravi Shankar performed at the festival in 1970 to great acclaim, and Fyffe has chosen to include his Sonata for Harp and Cello in Forest’s upcoming concert.

Ravi Shankar performing at the 1970 Shiraz Arts Festival

“They have amazing conservatoriums in Iran,” Fyffe recalls, “with lunchtime concert series that feature really cool contemporary stuff – music that I tried to perform at Melbourne Uni as a Masters student, but was wasn’t allowed!”

“It was a piece for saxophone and electromagnetically prepared piano. But at Melbourne Uni I was met with cries of ‘You can’t do that! You can’t touch our pianos in that way!’”

Fyffe found this injunction quite curious, given that we generally enjoy greater social and artistic freedoms in Australia. With eyes narrowed in thought, she says ‘I think it’s interesting that students at Iranian conservatories are able to play music like that, but in Melbourne we still face strong resistance.’

Making music in the face of resistance and censorship has also driven the creativity of many Asian musicians. When performing in Vietnam, Fyffe witnessed police shutting down performances if they deem the content too controversial or critical of the government. This has prompted creatives to find expression through music’s abstract nature. “With no lyrics, there’s no meaning… so it’s ok, right?!” she says with a laugh.

“We had been performing experimental improv by using the heads of our saxophones to blow into bottles of water,” she recalls. “You can get a range of about an octave and it creates a beautiful, haunting sound. This proved to be incredibly popular – even more so than our programmed concerts of notated music!”

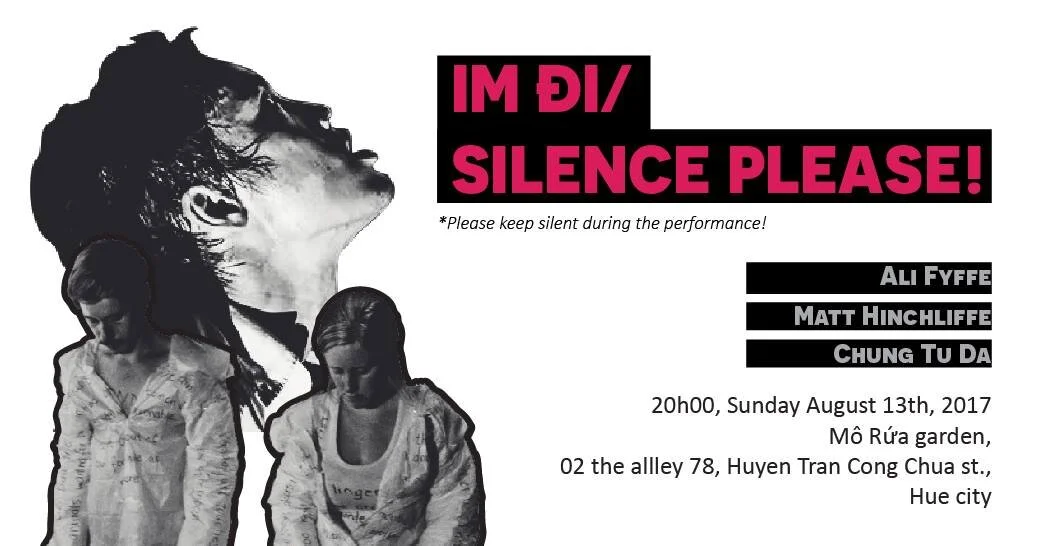

“On one occasion, we were playing at a venue in the city of Hue, in central Vietnam. The police turned up on the day of the show and questioned the venue owner for about three hours while we were supposed to be rehearsing.”

“The concert was called Silence Please! which the police interpreted as criticism of censorship. Ironically, this prompted them to try to censor the performance!”

“Eventually they demanded that we play for them right then and there. We didn’t have our instruments set up, so we just looked at what was to hand, which turned out to be a couple of violin bows, a few coat hangers and some wine glasses. We sounded the rims of the wine glasses and bowed the coat hangers making a haunting, ethereal effect.”

“The police were quite charmed and allowed the performance to go ahead, but on the condition that no audience was allowed in. Apparently, they now took issue with the idea of a gathering at this independent arts space rather than the music itself. However, they did allow for the performance to be filmed.”

To get around this directive, the event organisers came up with a cunning plan and spread the word on social media, as many anti-establishment groups in Asia have done in recent years.

“The venue owner put the word out on Facebook that everyone should come to the gig with their camera phones and only speak in English as they passed the police checkpoint, which had been set up near the entrance to the venue. Somehow, they all managed to convince the police that they were foreigners who had come to film the show, so it went ahead more-or-less as planned!”

One of the most exciting things Fyffe sees in Asian contemporary classical music is the rich influence of centuries-old native and traditional musical styles in modern notated works. And while this cross-pollination can lead to what Fyffe calls “structural westernism”, in that the system of western notation can often be ill-suited to traditional musical gestures, some composers have sought to push these boundaries as well. Luo Zhongrong, for example, developed a Schönberg-inspired 12 tone system adapted for Chinese music. His setting of the Han Dynasty poem Crossing the River to Pick Hibiscus will also feature in Forest’s upcoming concert.

Ultimately, for Fyffe, it is the freedom of improvisation that provides the most uplifting cross-cultural musical experiences. “You can improvise in any style, and good ideas can come from anywhere,” she says. “It’s a space where classical, jazz and traditional musics can all truly fuse together.”

This is true for both musicians and audiences as well, she explains.

“People can engage with the music on different levels. If I throw in musical gestures or licks from my own Western classical background, some people might get the reference. But then I won’t necessarily understand references to Kulintang gong music from the Philippines, for example.”

“With improvisation, people are always coming from different places, ascribing different meanings to the music.”

This allowed for a connection that was one of the biggest joys Fyffe experienced during her time in Asia.

“Even if you can’t talk to someone because you don’t speak the same language, you can still connect with them through improvisation and make music together.”

Fyffe sees this as a message of hope, particularly now as Australia’s geopolitical relationships in Asia become increasingly fraught. From a cultural and purely human perspective, however, Fyffe considers that we are closer to our northern neighbours than ever before.

“This concert is my way of trying to help things.” she says.

Asia in Focus will be presented at the Industrial School, Abbotsford Convent, 1 St. Heliers Street, Abbotsford, VIC, on the following dates:

Friday 16 July 7.30pm (Preview)

Saturday 17 July 7.30pm

Sunday 18 July 5.00pm

Preview - First release $10/Second release $15/Third release $20

Standard - $30/$35/$40

Concession (Student, Pensioner) - $20/$22.50/$25

Senior & Front line workers (Inc. hospitality, medical, education, transport workers) - $26/$30/$33

Under 15 - $15